Deep Bed Farming

The problems

Across large areas of Malawi, under the few inches of topsoil there is a heavily compacted layer of rock-hard earth. This is largely the result of long-term use of tilling hoes, human and animal footfall, and occasionally heavy machinery.

Plant roots cannot generally penetrate through this hard layer. Nor can air or water, which are necessary for the healthy living soils that support good agriculture.

If water were allowed to percolate into the ground it could be stored there long after the rains have stopped. Instead, it runs off the surface, taking much of the healthy topsoil with it. Devastating soil erosion can destroy soil fertility over the years.

This image shows a field on Zomba mountain, with maize ridges washed down the slope revealing the compacted hard pan underneath.

The United Nations' Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) in 2016 estimated that the average national soil loss rates in Malawi was 29 tons per hectare per year, with losses much higher in some regions. In that simple, devastating statistic lies a big part of the explanation for why Malawi is one of the world's poorest countries, and why hunger is so common.

This image of a sediment-rich river entering Lake Malawi shows where a lot of the country's valuable topsoils end up.

Other traditional farming practices in Malawi often exacerbate the problems. For example, dry maize stalks are often burned after the harvest, losing valuable organic matter and leaving the soil bare, which makes it vulnerable to rain damage and water evaporation.

The standard “ridge and furrow” method and the traditional "mound" farming method (pictured below), fail to combat compaction.

In fact, these methods can worsen the problem: for example, furrows are also used as footpaths which compact the soil, then ahead of the next planting season the soil from the ridges is typically heaped onto the furrows, ensuring that plants grow above a compacted layer. A network of footpaths can also become watercourses and soil-eroded gulleys when it rains.

Some farmers’ fields in Malawi are simply abandoned because they are assumed to be infertile.

The solutions

The Tiyeni approach contains several simple elements, which require very little in terms of material inputs, and which have repeatedly proven their effectiveness. We believe that whereas fertiliser may feed the plants, it is better and more sustainable to feed and nurture the soil.

The Deep Bed Farming (DBF) system draws on many of the ideas and concepts behind Conservation Agriculture, an approach originally developed in the Americas but promoted widely across sub-Saharan Africa in recent years.

Tiyeni has also added, tested and rolled out several important innovations that seem to work well in the areas of Malawi where we have tried them.

Step 1: Break up the hard pan

A first vital step is to use a pickaxe to break up the compacted hard layer underground.

Breaking up the hard pan already delivers powerful and immediate benefits, allowing roots, water and air to penetrate deeply into the soil, curbing or completely stopping soil erosion and immediately allowing deep and healthy organic soils to start developing.

Crops with deeper roots not only are generally stronger, but they can successfully deal with periods of dry weather, which have become increasingly common because of climate change. The deeper soils can also store much larger quantities of water, for longer, nourishing the crops far into the dry season.

This first vital step is key to building credibility for Tiyeni’s methods, and enthusiasm for farmers. To this credible “horse” we then harness further essential practices.

Step 2: Create the Deep Beds

Next is the creation of the Tiyeni Deep Beds. These are designed to minimise water runoff, to maximise water retention, and to prevent a new hard compacted layer from developing under the ground allowing roots, water and air to penetrate downwards on a long-term basis.

Careful measurement with line levels is used to create marker ridges exactly along the contour lines of the terrain, at intervals down the slope. Each ridge has a ditch running alongside it (the ridge is created with earth excavated from the ditch.) If there is a slope, the ditch is uphill of the ridge, so it serves as a dam for water after heavy rains: each ditch has closed ends, to prevent water spilling out and to encourage it to soak downwards. The ridge is then stabilised by planting with Vetiver, a non-invasive but deep-rooted grass that stabilises the ridge, and which is widely used for this around the world.

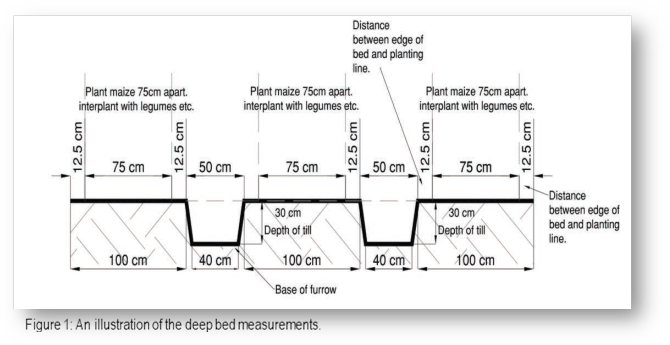

Between the spaced marker ridges, deep beds of soil are created, raised above the level of the surrounding terrain. These deep beds are a metre wide, enough for two rows of maize or three rows of smaller crops. A wider bed enables a greater share of agricultural land to be used for growing, as the ratio of bed-to-footpath is higher than with the traditional ridge (or mound) methods.

Once created, the Deep Beds are never trodden on again, so preventing recompaction.

Between each raised bed a ditch is also dug, also with closed ends and boxed at 3 or 4 metre intervals, which become a holding reservoir for water after heavy rain and allows slow percolation into the subsoil. The image below shows them in action.

Step 3: The Plants

The deep beds are planted with crops. The staple crop of maize is typically interplanted with beans, pumpkin, kale, soya, ground nuts and other local crops.

These nitrogen-fixing “green manure crops” enhance soil fertility and create shade which keeps the soil cooler and damper, reducing evaporation. They also help dissipate the force of big raindrops, protecting the soils from direct rain impacts, as this picture shows.

Interplanting can also help with pests and diseases, while consecutive cropping lengthens the cropping season and increases food variety leading to better nutrition. Deep bed Farming (DBF) increases the yields of all these complementary crops.

As the plants grow, weeds are cut or pulled up and laid on the surface as mulch, alongside crop residues, chopped Vetiver grass and other agro forestry residues. These augment the protection against rain damage, and also cool the soil and contribute to the organic content of the soils. The dead roots of cut weeds help the soil to breathe and microorganisms carry carbon and organic materials down into the ground.

Weeding is lighter work than digging, and whole families can help.

Meanwhile, excess foliage, crop residues, ash charcoal, maize husks and other food or household byproducts are made into compost, which can be supplemented with further additives if the soil is heavily depleted. **Animal (nitrogenous) manure** is added to help the composting process.

The recipe for this compost (pictured, source) is especially useful, since it takes as little as 21 days before it is ready to be added to the soil, normally as a top dressing.

Finally, Tiyeni organises a domestic animal pass-on programme of pigs or goats to first-time farmers, whose progeny are then passed on to other villagers, in an ever lengthening cascade thereafter. The animal waste is added to the compost, and the whole programme helps bring the village communities together because all are interested in the successful breeding programmes. This part of our work also helps encourage take-up of the Tiyeni methods.

Step 4: The results

Many Malawian farmers have achieved food security as a result of adopting Tiyeni's methods. Alfred Kapichira Banda, President of the Farmers Union of Malawi, uses Tiyeni's Deep Bed farming system himself and in this 2019 video shows the benefits. As he summarises: "This is marvellous."

The increased crop yields are generally repeated, year after year, and so far we have found that there is generally no need to break up the hard pan again after the first time. From then on, this becomes a form of 'no-till farming.'

This is a Malawian version of sustainable, effective, modern agriculture.

The challenges ahead

Tiyeni (of course) has always faced many challenges. Socio-cultural practices in any country are often complex and delicate, and Malawi is no exception. Our local team, sensitive to the issues and pitfalls, has through trial and error developed a system of Group Training which has highly effective in promoting acceptance of Deep Bed Farming, leading to its continued acceptance even after our extension staff leave the area.

A major risk is that farmers try out Deep Bed Farming, after hearing of it on the grapevine, but without the necessary training. They may cut corners and miss out crucial steps - whether it be breaking up the hard pan, crop rotation, or building the Deep Beds correctly. This could lead to crop failure, disillusionment, and the long-term discrediting of DBF, at least in that community. So it is essential that we are in a position to be able to cope with the burgeoning demand for training. More funding would enable us to spread the messages more effectively.

Further resources

Our updated 2023 Deep Bed Farming Field Manual.

DEEP BED FARMING - FIELD MANUAL

This video below provides a brief explanation of Deep Bed Farming.

Our Research page provides internal and external evaluations of the DBF method, as well as pointers for possible future research, and an open invitation to researchers to come and find out more.

As ever, more research is needed. We would like to see more and deeper research into how DBF works, where it works best, and how it fits with local conditions and socio-cultural practices.